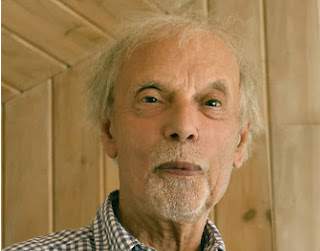

Otto Laske is a visual artist, composer, and published poet writing in English and German. His

visual art is entirely digital; his concert music comprises both instrumental and electronic works.

Given that his compositional career of 45 years preceded his turn to visual art (in his seventies),

his work shows strong influences of music-compositional thinking in that it emphasizes energy

flow, variations of density, conflict resolution, and contrasts in terms of color, line, and stroke.

Otto’s visual art developed out of animations comprising images, music, and his own poetry read aloud.

He initially exhibited specially selected animation stills as paintings. As time went on, he

increasingly embraced Klee’s notion of Aufzucht der Mittel (nurturance of the tools of the craft)

as the core of art making. As a result, his primary concern became the aliveness of the pictorial

space. For him, this esthetics entails freeing the elements of painting from subservience to

representational goals as much as possible.

Where are you from, and how has your educational background shaped your art making?

I was born under the Nazi-Dictatorship in the region of Silesia, now Poland. As a child of 8 ½, I was lucky enough to escape the Soviet Army and to become a West German citizen. At the time my family fled Silesia, my father was part of the retreating German army, a large part of which entered Russian prison camps 5 months later (May 1945). Although few returned from the Gulag, I was privileged to see my father again when I was 11, one year after my maternal grandfather, a school principal and broadly educated musician, sent me to Gymnasium as a preparation for college.

I think now that the refugee trauma in my family has a lot to do with the creativity I have exhibited in my life, so that my life’s difficult beginning was rather a gift to me. Having been able to follow my interests in an untrammeled way throughout my life today makes me feel very privileged. It strengthens my awareness of under-privileged lives around me, as well as my sense of the seriousness of art for the well-being of society.

Between age 20 and 30, I went from studying social sciences to philosophy, all along writing poetry (in German) which I began doing at age 15. Although a scoundrel music teacher made me give up piano playing at 11 since he thought me to be ‘not musical’, I took up music composition

on my own at age 24. In doing this I was again fortunate. I found a composer (

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=konrad+lechn+er) who accepted me as his student because he believed in my talent. He also led me to partake of an annual international music festival in Darmstadt, near Frankfurt, Germany (

Darmstädter Ferienkurse), where composers like Stockhausen, Boulez, Berio, Babbitt, Cage and others taught me how to break away from traditional (tonal) music.

When in Darmstadt at age 27, I met the German composer Gottfried M. Koenig (http://koenigproject.nl/) who a few years later, in 1970, invited me to work with him at the Utrecht Instituut voor Sonologie, The Netherlands, to undertake purely digital work in music composition and sound research. At that time, I had completed a Ph.D. in philosophy at the Frankfurt School with Th. W. Adorno (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_W._Adorno), and had left Germany as a Fulbright student to obtain a M. Mus. in composition at New England Conservatory, Boston, MA. My stay in the US had led me to switch from writing poetry in German to English as I continued to do into the 1990s.

The fortunate course of events mentioned above provoked and nurtured my work both personally and artistically. I seemed to have made the best of my childhood trauma, being active in poetry, music composition, and music research with computers. I was beginning to rethink musicology as a cognitive discipline based on Artificial Intelligence, and focused on the creative process in music. I began to realize that artistic work in the digital domain was process-, rather than structure-, oriented and had its own real-time aesthetics. I was eager to understand in what way computer software could revolutionize the creative process, not only in music but in all the arts.

In music, what did working digitally teach you about art making?

In the 1960s, work with computers became the medium par excellence for artists who wanted to break with tradition, not only in music, so that even the Darmstadt Music Courses of the 1950s and 1960s began to look traditional to me, given the exclusion of electronic music. Under the influence of using software in what was then called computer music, composers’ conception of the creative process underwent a change in the direction of experimental work, that is work without regard to hallowed tradition.

In music, this meant two things: (1) delving into the acoustic “partial” structure of sound, as well as (2) designing for each composition one’s own unique protocol or set of compositional steps. I did so by using G. M. Koenig’s

Project One computer program for music composition. (

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3679506). In Utrecht, where I worked for five years (1970-75), computers were used by both composers and visual artists. Clearly, traditional ways of art making had to be re-thought from a strictly structural point of view with the aid of software as a guide in, and medium for, compositional processes.

It took me some time to realize fully that the use of software in the arts was tearing down the conventional curatorial boundaries between the arts. The discoveries I made early on were more directly personal. They had to do with involving myself with the real-time compositional process in music from which I decades later drew consequences for my work in visual music (animations) and digital painting.

Below, let me summarize my discoveries:

1. Music composition, historically bound to notation, is now able of using the basic acoustic building blocks of sound called partials. The ‘partial revolution’ – just as the much later ‘pixel revolution’ -- changes artists’ mental process by enabling them to design their works from the top down. This meant they could start from abstract conceptual frameworks of their own invention (e.g., structure formulas) that a computer program would employ to flesh out the details within the framework they had designed, e.g., pitches, durations, harmonies, densities, and tempi. Since these details required a composer’s knowledge of acoustic and/or electronic instruments (in addition to knowledge of the computer), s(he) was challenged to refine and deepen her internal listening in order to find the (for her) optimal interpretation of the details a computer program had provided. Rather than automating the compositional process, computer software was giving rise to a new way of internal listening in which traditional auditory strategies were abandoned. As a result, a huge “ear cleaning” took place.

2. To provide details for a compositional design, many computer programs began to use controlled random. They enabled the composer to decide intuitively what degree of random a particular musical movement was to embody. Since such decisions depended on the “structure formula” a composer had initially chosen for a work, s(he) found herself bringing to bear on her creation all of here intuitive knowledge about acoustic structure she was capable of. Working in this way entailed that a composer could use more than a single work on the same structure formula (if she so chose), simply by interpreting program out from the formula in ways pertinent to a different set of musical instruments.

3. As a result, compositional thinking began to attach itself both to the highest level of the musical imagination and the lowest level of acoustic materials simultaneously.

4. Also, composers can dispense with notation, except for providing performance instructions for musicians working in real time where needed.

5. Composers can become animators by

visualizing their music through animations based on images of their own invention (

http://ottolaske.com/animations.html), such that their musical score provides the animation’s foundational structure.

6. Composers can become choreographers by applying algorithmically produced numerical to dance movements, leading to new ways of making non-traditional modern dances.

7. Composers can become visual artists once they find ways of linking their music to images of their own choice in a digital medium.

In short, it became clear to me that ultimately any material for art making could be broken down into its digital equivalents (e.g., partials or pixels) to supersede traditional ways of art making. The new software-based ways of working in the arts were giving rise to digital arts which are not bound to conventional manual tools or curatorial categories and will eventually create their own audience and market. All this amounted to the realization that there were no limits to artistic invention, in whatever art discipline one chose to work since all the arts are virtually connected.

When thinking of your work in music composition and poetry in relation to your visual art, what comes to mind?

Electro-acoustic music always attracted me because of the fluidity it is characterized by. I mean not only acoustic fluidity in real time (which is the hallmark of music), but also the fluidity of the work process that determines the structure of a piece of music in terms of its tone color, texture, and rhythm. Such music has a high degree of immediacy even in inventing it since one could easily test how it sounded right here and now without having to wait for some performer or conductor to become interested in it. In this sense electronic music moved the composer closer to being a visual artist, above all a painter who worked with time as an initially empty canvas.

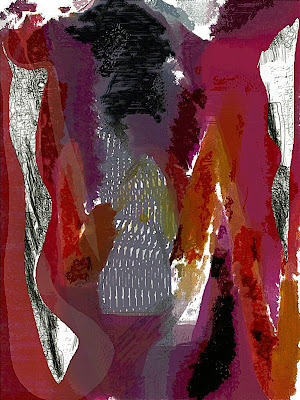

I found the same fluidity in real time when reading my or other poet’s poetry. Read aloud, poetry has its own acoustic structure quite independently from its content, or semantic structure that is also has. Conveying movement therefore became a focus also in my visual work, whether I emphasize color, line, or stroke. The works called ‘Lifelines 14’ and ‘Broader Strokes No. 17’ are examples of such fluidity. Pronounced visual movement of course invites its opposite, as demonstrated in ‘Broader Strokes No. 4’, for example. Fruitful tensions between movement and stasis are often ingredients of my visual work, as for example in ‘Broad Strokes No. 1’.

From a strictly compositional perspective, the process of making a piece of music (which can take weeks or months, even years) is, of course, dramatically different from writing especially lyric poetry as well as making visual art. Good lyric poems are given, not made, because they flow in one piece from a mysterious emotional source from the right hemisphere, and thus are rare. However, a visual work can equally be given rather than made, as I remember experiencing when producing ‘Broader Strokes No. 17’, ‘Brush Extensions No. 13’, and ‘Broader Strokes No. 4’.

It seems to me today that my original yearning in artmaking regarded the immediacy of feedback from what I was producing, in whatever medium that might occur, so that paper was always of secondary importance to me compared to the immediacy of aesthetic effect.

***

As is well understood, the way compositions start in different media is vastly different. While composing a piece of music for me often started with a purely structural, conceptual idea as to the balance of parameters such as pitch, duration, and tone color in a specific section of music, I experience beginnings of lyrical flow as visual, emotional, word-based, or coming from an unknown source beyond myself.

A feedback loop exists between the medium an artist works in and the inspirations that arise from, or relative to, that medium. Such inspirations are powerfully enhanced by software-based tools. Such tools give the artist the freedom to determine what part of his/her compositional process is taken over by software processes (e.g., controlled random), and what part remains controlled by the artists manually expressed imagination. The merger of intuitive and algorithmic work in digital arts extends to the artist’s intuitive decisions about when to call in software control, for what part or layer of the work in process, and even to what extent and for how long. Everything in art making converges on the moment in real time in which the artist finds himself at a particular point in time.

In

Studio Artist, the visual synthesizer I use (

https://synthetik.com/), controlled random -- first used in music composition by Xenakis in the 1950s and Koenig in the 1960s -- is an ingredient of almost every stroke I make, line I draw, and color I apply. It is a technique not confined to a single aesthetic medium in that it permits an artist to cross conventional boundaries between curatorially frozen aesthetic categories.

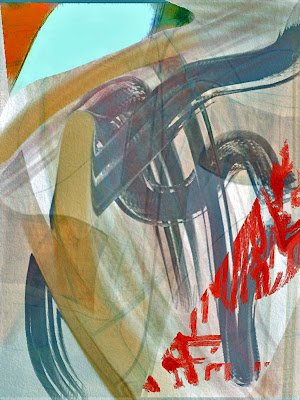

In my experimental way of working, a new work may emerge from a single brush stroke on an empty screen in real time that changes a previous, not fully crystallized intention of mine, or supplants it by a new intention. Such a brush stroke does not come out of nowhere but is the emissary of the task environment I have built up in previous weeks or months that I am no longer fully aware of, that has been stored in my software. Such a task environment is defined by ‘presets’ I have previously used, which I might have stored in the form of work sessions. Such sessions comprise images I have previously worked with or on, which are associated with specific brushes and color palettes. I am able to call up a previous work of mine from my library of works, an image from the internet, or a photograph or drawing of mine, and subject it to transformations such as filtering until the right visual configuration or color pattern for a new work moves into view.

In contrast to relying on previous work, I have the freedom to begin from scratch with whatever brushes, colors, or contours I come upon at a particular moment, and thereby discard influences or traces of work done previously.

What is your favorite medium within the digital visual arts?

For me, there are two such media: animation and painting. In the first, I can combine sounding music, read-aloud poetry (or other text), and images of my choosing, including (parts of) paintings. While the resolution of images in animations has so far not always been optimal, the relative fuzziness of images is nevertheless evocative and supports telling a story.

Digital painting, my second medium of choice, is open to the inclusion of both photography (e.g., Focus of Devotion) and graphics (e.g., Brush Extensions No. 13). In addition, digital paintings can be structured based on multiple layers of subtly merging shapes that frame linear and color configurations, as in the work ‘Passover’. All these mixtures defy conventional curatorial categories, and point to new kinds of aesthetic synthesis that have become possible in digital arts.

What are your uppermost goals and challenges when you make art, especially visual art?

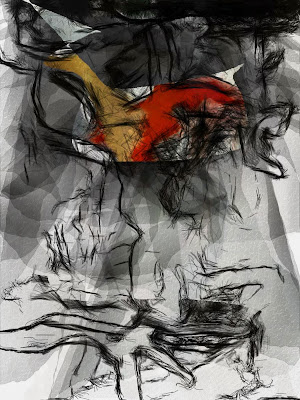

In my nearly 70 years of work in the arts, I have encountered dramatically different provocations calling for art making in myself. Some of these have been purely emotional (one might say ‘unconscious’), such as those propelling my German and English poetry. Others have led me to designing musical scores top down based on a high-level structure formula for relating musical parameters (as used in work with Koenig’s Project One). In my visual work I have defined brushes so big they can fill an entire canvas by 3-4 stylus gestures on my digital tablet, as (for instance) in ‘Broader Strokes No. 14’. Making such a work is highly meditative. Conscious and unconscious aspects of mind merge therein in always new ways. This is so because the artist, working at a high level of self-awareness, is simultaneously led by his sense of form, weight, and balance most of which resides in the bodily unconscious that pervades his or her whole person.

There is a somewhat inscrutable link between such contrasting provocations and the goals and challenges an artist may respond to.

The older I become, the more are my aesthetic goals determined by my search for an economy of means, even when the resulting outcome of my work later seems to contradict that intention. I have always been guided by what Paul Klee referred to as “the nurturing of artistic means” (die Aufzucht der Mittel). As I read this phrase, he wanted it to lead artists to deeply engage with the elements of art making – colors, lines, textures, and rhythmic patterns – so that they would determine by themselves what was to be done with/by them in a particular moment of real time. He wanted to discard from the work process anything but the very means by which a work is to be produced, such as ideologies, political motives, and visual models from the past.

‘Economy of means’ is of course just an abstraction. In my experience, it becomes possible to the extent that an artist engages in depth with his or her own internal dialogue. Such a dialogue gains in structural quality to the extent that it merges with what the tools used in real time demand of the artist at every moment of the work process. For me, to develop a sense for linking the means of art making (tools) to one’s internal dialogue with the materials chosen for making a specific piece of art is the foremost purpose of art education.

As to artistic challenges, even purely aesthetic ones seem to me to be too numerous to name, given that they are different in each task environment and medium. For me, the uppermost challenge has been to bring the pictorial space to life by freeing it from intentional representational goals. This does not entail that representational elements are ‘forbidden’ to appear. It only means that they should emerge unplanned and should never assume a role other than to point to a non-representational totality. (For examples of following this credo, see Intrusion, Focus of Devotion, The Colossus, The Art of Messaging, Broader Strokes No. 12).

What keys to being productive can you share with us?

Rather than seeing artists as an elite, I see them as craftsmen and -women who work predominantly from the brain’s right, rather than left, hemisphere, -- that is, intuitively and with a holistic outlook on the work to be done. Such people’s left hemisphere (where logical thinking resides) is only an interpreter of what is constantly given them by their right hemisphere, contrary to what we see happening in business and society at large. For this reason, working with algorithms in artmaking has for me always been a strong form of critiquing the algorithmic controls we as members of society are increasingly subject to. By using algorithms in a way subject to their own intuition, artists can show the public that other than purely logical and practical goals exist for using software.

For me, art making is one of the most powerful ways of strengthening a holistic and empathic way of encountering the physical, and even the social, world we are embedded in. It is also one of the most powerful ways of strengthening people’s internal dialogue with themselves that is presently at risk for being drowned-out by mind-externalizing gadgets used for the purpose of pre- or re-programming entire populations in a politically risky way.

***

For me, creativity is a buzzword that in its positivity hides the profound personal disturbance that underlies it, whether that disturbance is acquired or innate. The term covers up the fluidity of thought and internal dialogue with oneself that naturally seeks to express itself in all people. In my own experience, creativity is the result of finding oneself living in a beleaguered state, whether internal or external, from which one needs to extract oneself. It is thus different from productivity which is merely a potential result of creativity flowing from the strengths of the disturbances one experiences.

In this sense, then, there is little to share other than the works themselves which bear the imprint of the attempt to liberate oneself from hidden or evident schemata and constraints, most of which tend to be secretly oppressive. Doing so requires using means of navigation between the ordinary and habitual, on one hand, and the outrageous, on the other.

Praise should be given to the seemingly simple elements we call color, sound, rhythm, and line which, when internalized by an artist in their purity, can liberate him or her from oppression (except death), and can potentially perhaps liberate also those who approach his or her work with an open, unbiased mind.